Photo by Pixabay

Every time you light your barbecue, you’re igniting a medley of exciting scientific processes. These phenomena and reactions combine in deep and unexpected ways. Safe to say, there’s a lot more to that mouthwatering lamb chop or chargrilled banger. Much more in fact, and it pays to know exactly what happens every time you cook with a barbecue. Getting into the nooks and crannies of the science of grilling could lift you from BBQ dabbler to maestro. So, grab your tongs, water pistol, and makeshift hand fan as we explore the sizzle and science of BBQs.

Gearing Up for Grill Glory

Charcoal, gas or infrared? Choose your BBQ fighter carefully because each format brings a different scientific benefit to the table.

Photo by Gonzalo Guzman

Charcoal Barbecues: The David Attenborough of Grilling

Good old charcoal grills are the classic way to barbecue and a hallmark of summertime. From a technical point of view, they’re also super versatile, allowing you to get crafty. Once you get familiar with hotspots, you can work out how to configure your grill. Maybe there’s a thick lamb chop that could do with a slower, indirect cook. Or perhaps your steak needs direct volcanic heat to sear up. There’s the smoke factor too, caused by lipids, amino acids, and sugars dripping from the meat onto the coals. That flavour-loaded smoke is then absorbed by your food, infusing it with taste sensations many barbecuers can’t live without.

Photo by Joe Ross

Gas Barbecues: Consistent like Alexander Armstrong

Purists have been known to turn their noses up at them, but gas barbecues bring a ton of technical benefits. A big one is how quickly you can get up and running. There’s no fire-lighting, fanning, or fretting because the coals are still black. Instead, you can get cooking in under ten minutes. The convenience makes it possible to have a barbecue any day of the week, a bit like Pointless. You can also control temperature with ease, and this is vital for chefs who want optimal doneness. Naturally, there’s going to be a lot less smoke from juices dripping from the grill. This can be good if you’re keeping an eye on potentially harmful polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

Image by Dall-E

Infrared Barbecues: Clinical like Jimmy Carr

While the traditional debate was always charcoal vs. gas, infrared grills have arrived on the scene to complicate matters. Infrared grills can operate at extremely high temperatures, well above 370°C. This kind of reliable ripping heat is perfect if you need to sear that ribeye for mere seconds on each side. If cooking is more science than art for you, infrared has a lot of benefits. A big one is the uniformity of heat distribution for an even sear. If you want to achieve the Maillard Reaction with clinical precision like a Jimmy Carr quip, infrared is the way to go.

Kmecfiunit, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

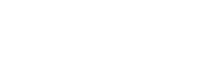

Heat Wave! The Three Musketeers of Heat Transfer

Early in your grilling journey, it pays to understand the various ways heat is transferred to your food. We’ll start with conduction, which is heat transferred via direct contact. With a barbecue, the contact will be the surface of the grill, or via a special accessory your barbecue may have, like a sear plate. Heat always moves from hotter to cooler surfaces. The contact with, say, a drumstick, will give it those telltale sear lines, caused by pyrolysis or caramelisation. Then there’s convection. In this process, heat is transferred to your chicken leg by an agent. This is usually the air constantly circulating in your barbecue, forced upwards by those coals. It can also be oils or water on the surface of your food. You can use convection to cook the upper side of your meat by putting the lid on. Here convection will transfer heat to the outside of the meat, which will then travel to the inside via conduction. Finally, you’ve got radiation. Now, nobody’s talking about nuking your burgers. This is all about the direct heat reaching your burger via electromagnetic waves. You can feel them whenever your hand passes over the coals or infrared element. One for all and all for one, the three types of heat work in perfect harmony in a BBQ.

Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

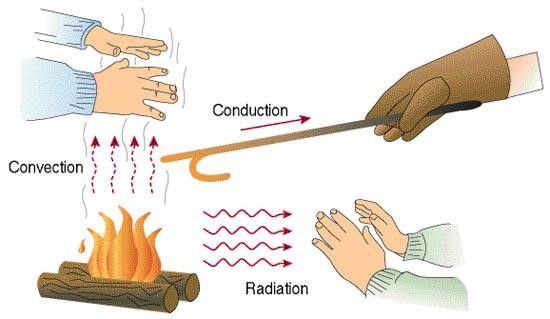

The Maillard Reaction: A Smoke Symphony & Flavour Alchemist

This transformative process takes place when proteins and sugars interact at high heat to produce new molecules. The resulting molecules keep reacting, giving rise to hundreds more compounds known as melanoidins. These are super varied, hard to define and often occur in the tiniest amounts. That huge cast of flavour compounds is responsible for a galaxy of distinct tastes and aromas. They all manifest in dense rings on the surface of the meat. Reflecting light as a brown colour, melanoidins are concentrated goodness. For this flavour alchemy, you first need heat, well above the boiling point of water. The Maillard Reaction is one of the many reasons barbecuing is such a fantastic way to cook. Dryness is another factor—less moisture means more compounds ready to transform into pure flavour, so a little dabbing goes a long way.

Smoke & Mirrors: Crafting Aromas with Flames

Barbecued food also tastes amazing because of the smoky flavour. It’s not just the stream of smoke wafting up from the coals but the makeup of the food that creates this perfect partnership. Most meat has a relatively high fat and water content. Both of these have a knack, in their own ways, of binding with the cloud of flavourful molecules present in wood or charcoal smoke. The key chemical known for that smoky fragrance is syringol, while guaiacol gives you that smoky taste. Being non-polar, fat binds easily with other non-polar chemicals, while water is polar and does the same with molecules that have a positive charge. So they’re the perfect team for absorbing all that smoky joy.

Wood Chips: Subtle Flavour Bombs

One way to take your smoke game to the next level is to start adding wood chips to your charcoal. Wood is packed with its own volatile flavour compounds, while charcoal is 99% carbon. It pays to be picky about the kind of wood you’re burning under your grill. In fact, it’s something you can factor into your recipe when you’re planning your barbecue. For instance, beech and alder, common in the UK, have a subtler tone. This is ideal for food with delicate flavours, like vegetables and fish. Then if you’re cooking white meat like chicken, you could go for something with more body like maple, cherry or apple wood. Finally, for the fullest flavour, perfect for hearty red meats, you’ve got oak or chestnut. In this category, mesquite is trickier to find in the UK, but well worth seeking out.

Georgi Kirichkov, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Juicy Triumphs & Health Harmony

Fat Fantastic: Choreographing the Juiciness

When it comes to barbecuing, fat is your friend. Get the right kind and amount of fat in your cut, and it will hit the spot. Fat enhances the irresistible BBQ aroma, is laced with flavour-contributing volatile compounds, and the accompanying moisture makes it all extra satisfying to eat. Heat degrades fatty acids into volatile compounds, big contributors to flavour. Fat is also great at absorbing molecules from smoke, enhancing flavour on yet another level. In short, all of this gives you the multisensory symphony that is a prime bite of barbecue.

The Art of Resting Meat: Patience is a Virtue

Resist the temptation to attack that steak like a rabid meat hound. You’ve got to take the time to let the cut rest. Why? It’s all about moisture preservation, keeping all of that magical fat in the meat, rather than all over your plate. High heat forces the fibres of the meat to contract, driving all of the juices away from the edges of the cut to the centre. If you wait ten minutes, you give the muscle fibres on the edge of the cut time to expand, welcoming all those juices back to where they belong.

BBQ & Health: Navigating the Grill Landscape

Fat is that fun loudmouth friend who can do with some time on mute occasionally. Clearly, there’s a balance to be found. In red meat, the recommended fat content weighing flavour against health considerations is just over 7%. There are other health details to think about, like char, or pyrolysis, and not to be confused with the Maillard Reaction. Just the right amount, as you get with gorgeous caramelised grill marks, adds a new kind of flavour and a lovely crispy texture. Too much, or the wrong kind of carbonisation can be carcinogenic, so not a great idea. Getting scientific about barbecuing can help you fine-tune details like cooking temperature, rotation, or direct vs. indirect heat, achieving that Goldilocks level of char.

Pohled 111, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Beyond the Basics – For the Connoisseurs and Innovators

Molecular Gastronomy: The New Frontier in BBQ

If you want to go all Heston Blumenthal at the grill, there are lots of avenues to explore. Barbecues in the UK are mainly used for cooking food quickly at high heat, which isn’t ideal for all cuts of meat. Techniques like sous vide and the reverse sear come into play here. For instance, you might immerse a dense slab of sirloin steak, sealed, in a water bath to achieve optimal doneness throughout. And then, after patting dry to optimise the Maillard Reaction, you can give it a minute or two on the barbecue. The same applies to the reverse sear, where cooking at a low temperature gives you evenness before the high-heat finale on the grill.

Flavour Layering: Rethinking Marinades and Seasonings

Marinating your meat? Consider using a marinade injector to get the marinade deeper into the meat. Using a dry brine is always a good idea for locking in moisture. Instead of sticking with simple salt and pepper, improvise with flavours that will complement your meat, and even the kind of wood you’re planning to smoke with. Even when your food is about to leave the grill, you can experiment with on-grill seasonings, applied in the seconds before that resting period. These will interact with the last licks of heat, and mingle with the Maillard Reaction after it has formed.

DIY Grill Hacks: The Inventor’s Playground

You can apply the spirit of deconstruction to your grill. One handy way to get a more even cook is to blend convection and conduction by placing an aluminium roasting tin with a rack on top of the grill itself. This little hack disperses the heat more evenly and takes the guesswork out of barbecuing on charcoal. A tin is useful for thicker or tougher cuts better suited to a longer cooking time. Then, when you want that classic barbecue sear, you can move the meat from the pan to the grill. You can also avoid a lot of cleanup this way. To truly harness the power of convection and venture into southern-style BBQ, you can also convert your barbecue into a smoker. For this, you’ll need aluminium roasting tins, your choice of wood chips, and a thermometer to monitor the temperature inside. To keep things simpler, maybe pay more thought to the distribution of your charcoal. With a bit of craft, you can create a range of different heat zones, suitable for things that need a quick cook or require a little more time on the grill.

Image by RDNE Stock project

Conclusion: Hanging up the Apron

So the grilling odyssey is almost at an end and it’s time to plate up. We’ve talked about volatile compounds, the second law of thermodynamics, and the Maillard Reaction. And we only had to use the word ‘mouthfeel’ once. Well, twice now. How do you intend to apply your chemistry or physics knowledge at the grill this summer? Perhaps you’ve already found ways to apply scientific principles and insight to elevate your barbecue. If so, don’t hesitate to share them.

Recommended Reading & Resources

Books

- Flavor by Fire: Recipes and Techniques for Bigger, Bolder BBQ and Grilling, by Derek Wolf, Steven Raichlan

- Meathead: The Science of Great Barbecue and Grilling, by “Meathead” Goldwyn

Forums

- UK Barbecue Subreddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/UKBBQ/

- The British BBQ Society: https://bbbqs.com/Forum/

Webpages

- National Library of Medicine: The Role of Fat in the Palatability of Beef, Pork, and Lamb: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218173/

- PBS: The smoky science behind what makes food grilled over an open flame taste so good: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/the-smoky-science-behind-what-makes-food-grilled-over-an-open-flame-taste-so-good

- University of Richmond: BBQ Science: The chemistry of cooking over an open flame: https://urnow.richmond.edu/features/article/-/21609/bbq-science-the-chemistry-of-cooking-over-an-open flame.html

- The British Heart Foundation: How to Have a Healthy Barbecue: https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/nutrition/how-to-have-a-healthy-barbecue

- Modernist Cuisine: The Maillard Reaction: https://modernistcuisine.com/mc/the-maillard-reaction/